Objectivity is a key prerogative in journalism.

Everyone knows that the best possible way to be objective is to attempt to stitch together a nonsensical middle-ground stance between two entirely incompatible ideas. However, in some cases journalists are forced to use the second best approach to objectivity: heavily edited short form debate.

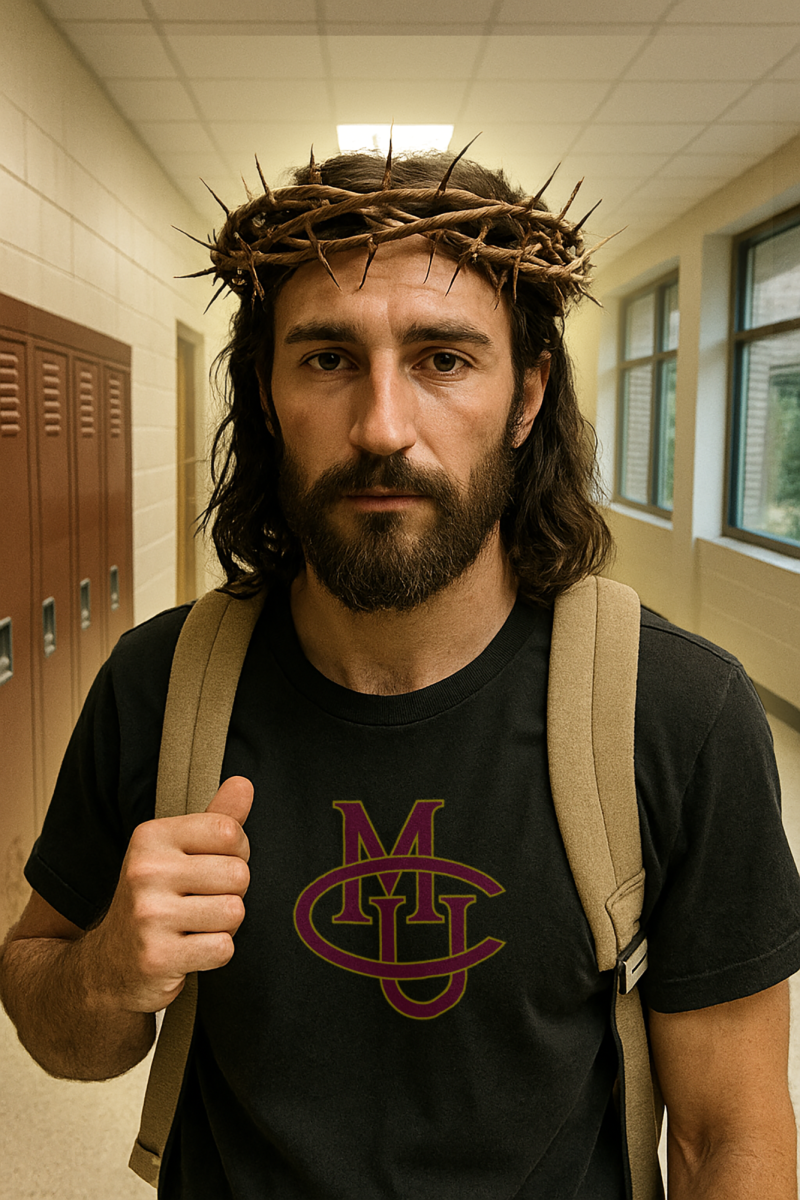

We asked Colorado Mesa University (CMU) economics professor Dr. Schush Nerdington who’s written 24 scholarly essays and two doctoral theses on the subject of educational economics to summarize a book’s worth of information on the spot.

“Before we examine our professors’ salaries, there are many questions we need to settle first. For one, how are professors’ pay rates determined? Professors are an exception compared to the rest of the educational field because they’re paid by the university itself-a private institution-rather than the district-a public institution-as such, their pay is technically subject to market fluctuations. Yet there’s something of a phenomenon in that their pay doesn’t actually fluctuate this way. In many ways, the plight of CMU professors mimics the plight of Mesa county and the Western slope as a whole-” rambled Dr. Nerdington before we cut him off.

We were also questioned by CMU economics sophomore Richard Wurstwright, who spends his and everyone else’s tuition money arguing with professors about their area of expertise for entire periods.

“First, CMU professors are paid whatever the market decides, no more, no less. If a professor isn’t happy with their pay, they just need to move their entire family across the state to teach at some other institution. Second, CMU professors are nerds, they’re old, they’re weird and they grade some students poorly just for disagreeing with them vocally at all times every day. So I’m not saying they should make less, but if they did, I would act very smug about it,” Wurstwright half-yelled.

When asked to reply, Nerdington gave a long-winded and scholarly retort which I, as a journalist, am entirely capable of paraphrasing without losing any nuance. Nerdington said Wurstright’s assertions were too simple and also said the word ‘underpinning’. His cheeks also wobble kind of funny when he gets really serious. Wurstwright then responded by pointing out a very small, highly semantic error Nerdington made and harping on it so much that Nerdington couldn’t get a word in, and the two had to be separated once class had ended.

Unbiased takeaway: By taking an issue he has no personal stake in and saying the most brazenly wrong and hateful thing he could get away with, Wurstwright made his opponent frustrated and flustered about an issue that personally impacts his livelihood. Wurstwright then expertly exploited the fact that his opponent would have to spend a lot of time making his argument by nitpicking tiny details to eat away at that time. Wurstwright won the way he always does, by default.