There’s a dissonance with living in a failing body.

You don’t wake up and go “oh, I’m slowly dying, and recovery is a senseless dream.” It’s more like a painting in the back of a selfie: it’s always there, pressing on, but not the focus of the image. Soon enough, it becomes a source of will, pulling power from moving in a body that struggles to move without the burning power of emotion.

Everyday I rot. It’s honestly not that bad anymore—in isolation.

Alone in my room, the numbness of my numbs all but in the light pains of nerves are there. But there is also the soft touch of a blanket, the purr of a cat on my lap. I can easily move to grasp my phone, boot up my computer or read another book—or perhaps a tome, if old enough—to occupy my time. They say on average people only live 4,000 weeks, and so to say, we are those 4,000 weeks. I don’t know if I even have a full cup of weeks, yet I am happy to say it does not bother me one bit.

When I leave my space though, or even dare to exist online, the simple happiness of existing becomes a contention.

Some people dare to call it a persecution complex—truly, it is not. In my first days of attending CMU Tech, one of my classmates dared to tell me it was vaccines and a lack of yoga that caused my body to bend to rot. He then pointed to a young girl in a wheelchair and told me to be grateful that I wasn’t “like that thing.” Similar comments are often told to students with disabilities, much to our dismay.

Being a thing, an object of inconvenience, is the most heartbreaking aspect of disability. Even with Educational Access Services on campus, daily experience is a struggle, especially with ableism often not taken seriously by Colorado Mesa University. Under the guise of free speech, some students are forced to listen to bigoted and ignorant comments about our disabilities.

The hardest part of disability, that usually only we know, is the eternal struggle of relationships. Of spaciality, moving in a world that wants to shut you away. I still wonder how many people truly know that if you’re on social security for disability, you can only have up to two thousand dollars in your bank account—and you can’t get married, less you lose your benefits due to joint income with a partner. All the more it stings when someone decides to call my kinsmen a burden to the world they exist in because they cannot work. In a world geared for production, disability is seen as a defective cog instead of disabled people.

The most terrible thing about disability is how the world does become, in part, tarnished. People who call themselves good will tell you how your body is the problem, that some yoga and snake oil diet will cure you. You’ll be told to quiet down your screen reader because it’s “annoying”, or be told that your mobility aids are in the way.

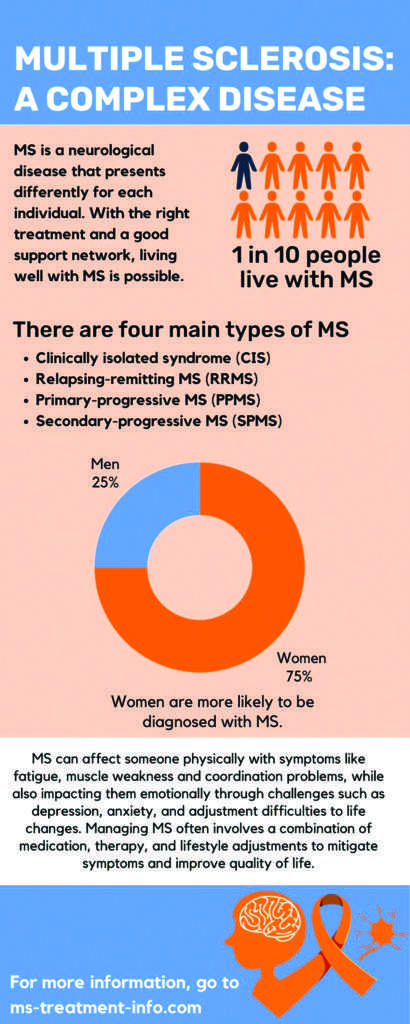

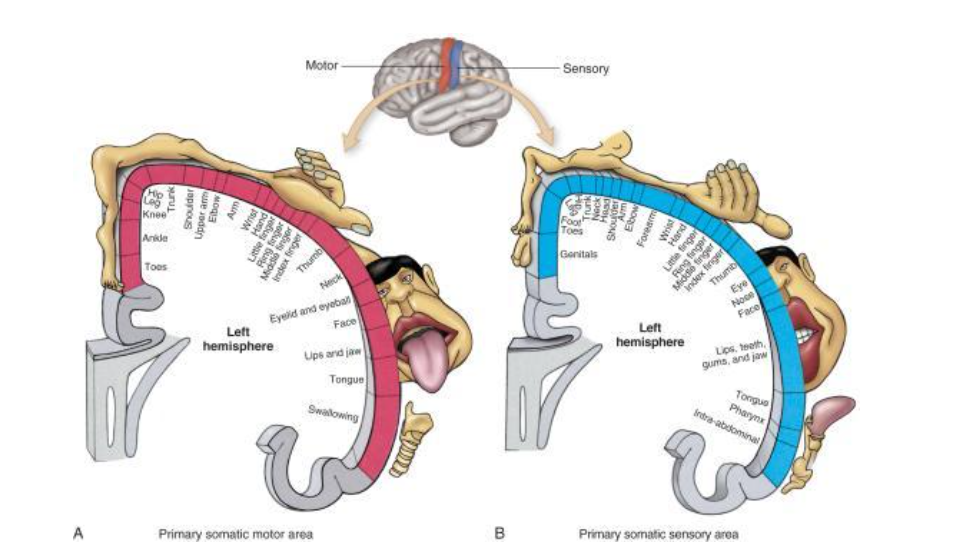

I would likely benefit from a cane—multiple sclerosis causes dizziness—but I do not use one. I could request it or even buy one, but truly utilizing cane would be difficult. I fear people stealing canes or poking fun at them, as my friends suffer themselves from classmates and colleagues harassing them for using a cane. Classmates often do not understand the gravity of my own rotted body, the multiple sclerosis in my nerves.

Nothing will stop us disabled students, especially as succeeding with disability is both a rebellion against this ableist society and also a mark of our own greatness. However, campus culture should continue to push to understand disabilities—and the physical and mental challenges they bring. Physical aids, screen readers and other aids would be much more bearable to use in public if others were much more compassionate rather than cruelly curious.