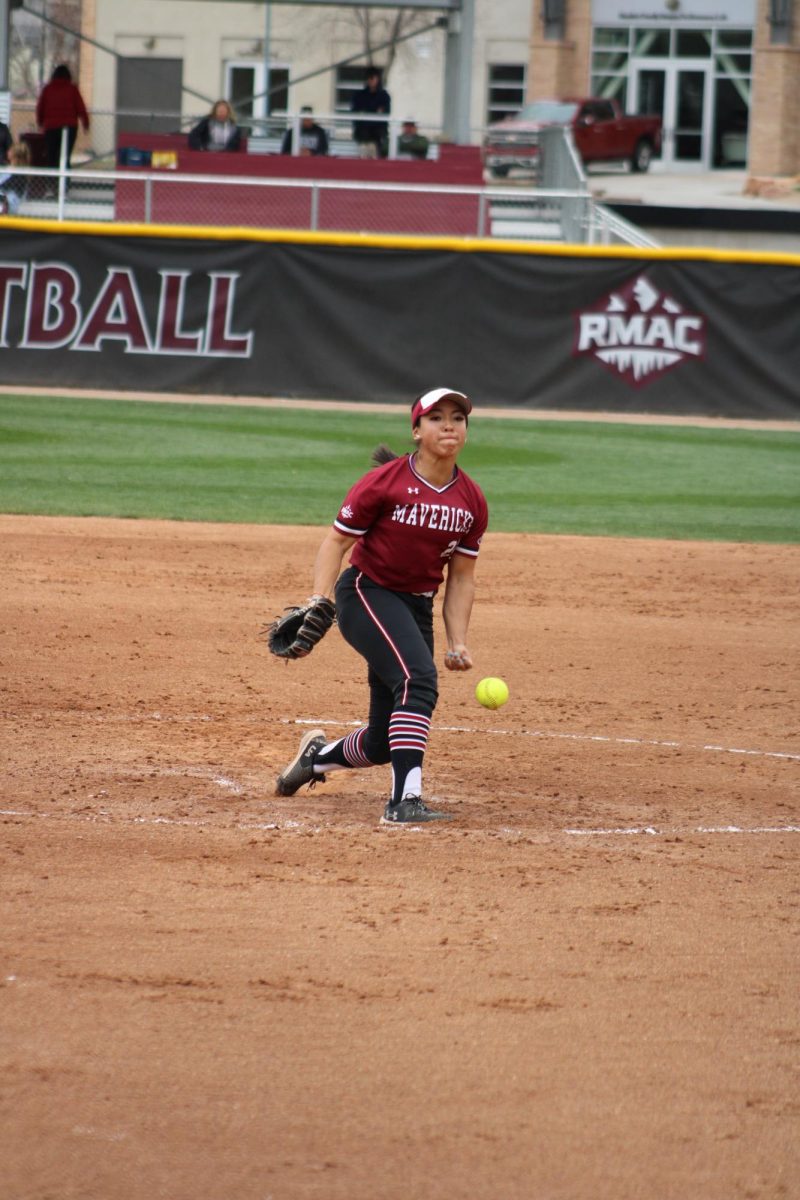

by John Cusick

I’m an NCAA athlete. And I am currently waiting for scholarship funds to come in. I’ve never had the problem of waiting around for my refund from Colorado Mesa University. However, a chord was struck with me the other day as I went for a run with one of my teammates. We were talking about NCAA athletes and the a few years removed discussion of the then University of Connecticut’s Shabazz Napier. At the presser before the national championship Napier talked about how there were nights where he would go hungry but still be expected to perform at an elite level. I’m not asking for the NCAA to start giving athletes more money or whatnot. What I am concerned with is the recent revenue reporting of the University of Alabama. Per Alabama’s recent release of reports, the football program reported $103.9 million in revenue. Again, that is the just the football program. It also reports that there was a $47 million profit, up 3.6 percent from the previous year.

The idea of Alabama athletes sitting at home in their dorm rooms starving for food seems impractical given their recent success. But the idea of giving student athletes, that drive revenues upwards of $50 million a year, some extra money so that they can continue to improve in the world of academia and on their preferred playing field doesn’t seem so ludicrous. Napier said in 2014, “I don’t think you should stretch it out to hundreds of thousands of dollars for playing, because a lot of times guys don’t know how to handle themselves with money.” That may one of the most accurate statements that has come from a student athlete.

A level of concern comes with giving student athletes more money. Most people will say they don’t deserve more money because they are given access to a free education. That is right. There’s a clear difference between student athletes and regular students as the schedules are more rigorous and they are held to a higher standard due to their representation of the university on a national basis. An article from Bloomberg talks about the revenue income for football programs around the country. In 2015 the NCAA granted autonomy to the Power Five conferences (Atlantic Coast, Big Ten, Big 12, Pac-12 and Southeastern) which gave them the ability to determine their own rules on financial aid and insurance. There was an added $2,000-$6,000 addition that helped where traditional athletic scholarships fell short (Bloomberg). That looks great, right? That’s what I thought too. Then I found an article from ESPN that showed in the 2014-2015 fiscal year, the Power Five conferences reported $6 billion in revenue. For comparison sake, the rest of the NCAA made $2 billion. That’s $4 billion more for five conferences.

There is not a certain way to go about giving athletes more money. Napier is correct in not asking for “thousands or hundreds of dollars” but there should be a stipend in which an athlete can use that money to buy groceries or eat. With as much revenue coming in for these conferences can the NCAA sit here and say the livelihood of players is less than that of making money. I personally believe that making sure that these athletes can compete at a high level is crucial. The money being invested in athletic facilities also needs to be invested in the athletes.