Teagan Meens

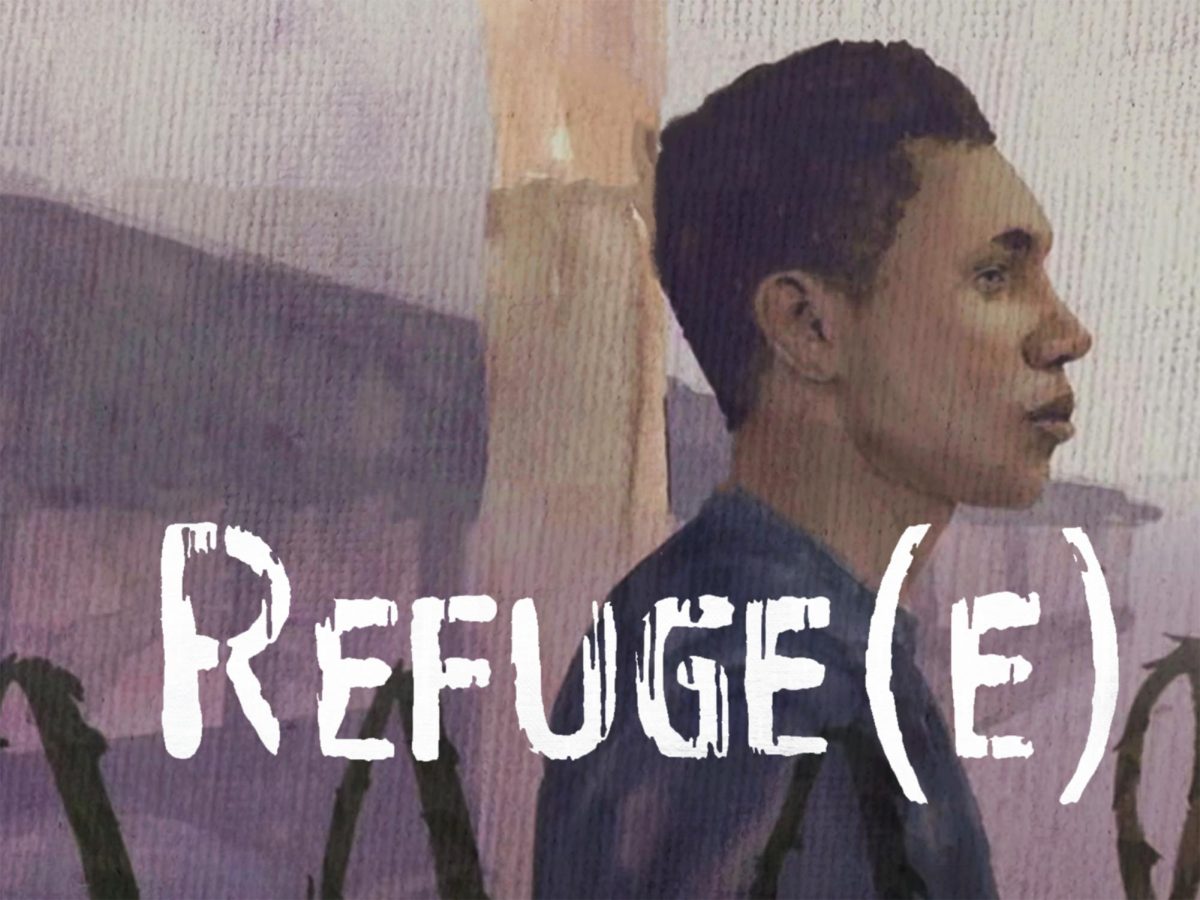

“Refuge(e),” a documentary highlighting the experience of migrants who faced imprisonment when seeking asylum in the US, was screened at CMU on Sept. 25. It launched a successful divestment campaign in for-profit prisons.

The US has declared war on migration, and Sylvia Johnson’s documentary, “Refuge(e)” captures the stories of asylum seekers in New Mexico. Caught in the crossfire of the Trump Administration’s so-called “invasion,” two asylum seekers from Africa are followed throughout the documentary. They were criminalized for legally seeking refuge in the US from persecution and violence in their home countries.

This story came to Johnson when she was working as a translator for a southern New Mexico law firm that represented migrants who applied for asylum in the US. Although this documentary was released in 2019 after two years of production, she said that the stories are even more important now.

“I wish with all my heart that this was not relevant right now,” Johnson said in a panel discussion following her film.

The criminalization of migration is a divisive and subversive topic. Johnson’s bravery to tell these stories and expose the transgressions against migrants at the hands of the for-profit prison system is not often heard. These are just two men among the millions that have been subjected to the dehumanization of the US migration process.

Detention, regardless of the circumstance, is the new normal for asylum

seekers and migrants in search of a better life in the US. Although these two men came into the country legally, they were held in a for-profit prison for months while their asylum case was processed.

The illustration conveyed dismal descriptions from the men of the detention centers as deplorable and miserable. Their voices recounted the conditions, while illustrations sketched out cramped cells, shackles and scenes of forced labor.

The most powerful moment came when one of the men was depicted receiving the call in prison that their asylum had been approved, and that he was going to be released. A blank screen was filled with the sounds of relieved sobbing. The decision not to include any visuals during this scene underscored the weight of the conversation.

Johnson’s first foray into illustration was a product of limitation. She was unable to capture anything but words from Alpha and Zeferino about their journey to the US, as well as the experiences that they had while detained in a for-profit prison in New Mexico. Johnson described the use of the watercolor-style animations as freeing in many ways, because of the artistic liberty it gave her over the visual aspects of the story.

A map was used to demonstrate the scale of the journey from Africa to the US. It sequentially highlighted the 10 different countries that one of the men passed through before getting to America. The most treacherous and harrowing part of the journey, walking the Darién Gap

between Panama and Colombia, was given specially illustrated attention to highlight their encounters with death and violence in the unforgiving rainforest.

The animation was well-balanced.Johnson said that if she could have, she would have used more of it in the film, however, it was too expensive. It may have been a blessing in disguise, because too much animation could have caricaturized the men and taken away from the severity of their stories. Conversely, too little animation could have easily made it seem disjointed and offhand.

The editing was careful and well-paced. Although it was a shorter film, the stories didn’t feel rushed which demonstrated a sense of respect and reverence for the plight of Alpha and Zeferino. Johnson relied heavily on their interview dialogue, switching liberally between the actual interviews, illustrations and informational cuts.

Prominently, this centered Alpha and Zeferino as the narrators of their own story. This mindful decision elicited sincerity, authenticity and acknowledged the harm that can come from speaking over others or trying to tell their story for them. Contextual information was provided but only as text on the screen. During the panel, Johnson stressed the importance of leveraging what privilege she has to uplift the stories of vulnerable people.

Johnson’s call to action was direct and clear— there must be disinvestment from for-profit prison systems, and advocacy for our world’s most vulnerable people. She explicitly named the prison corporation CoreCivic in a bold move that could be viewed as a threat. Highlighting harm, and potentially impacting profit margins, are easy ways to get a target on your back.