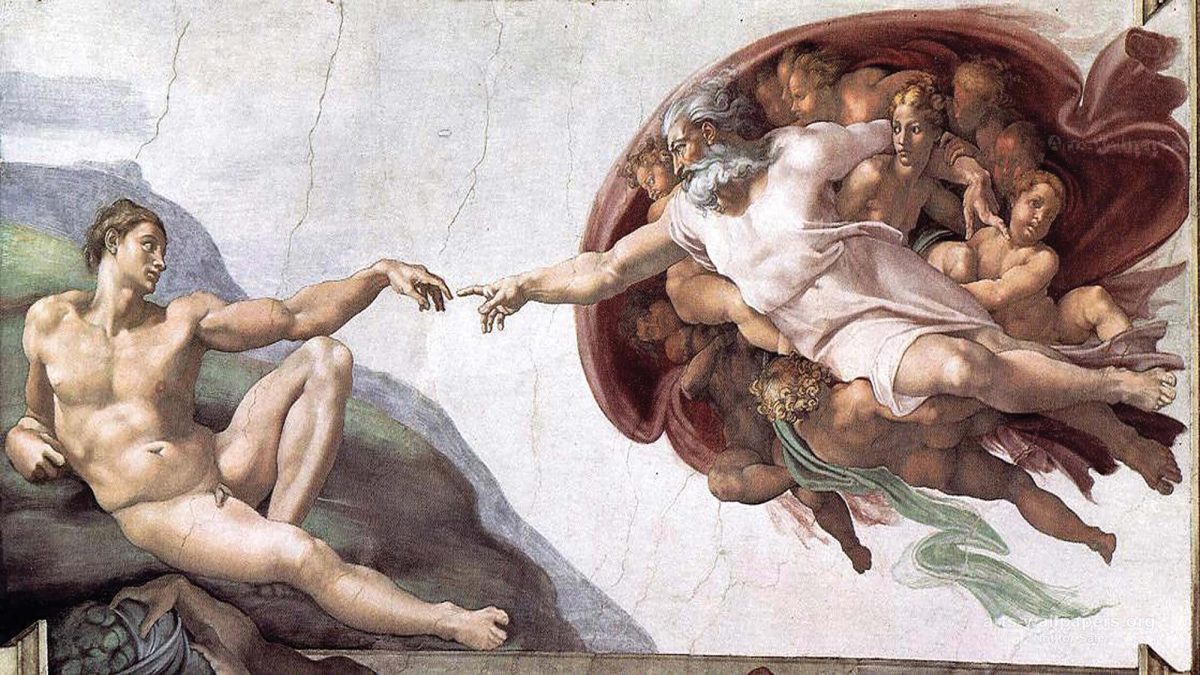

The Creation of Adam, painted by Michelangelo during the 16th Century is part of the collection of numerous paintings that make up the Sistine Chapel ceiling commissioned by the Catholic Church.

Even if there is a broad consensus that capitalism is harming art, reality is more nuanced. Throughout history, capitalism was never absent from art. Artists never stopped living, eating and procuring materials to create art. Patrons, finance and public demand never stopped dictating what art would be created. When we speak in terms of how capitalism has “destroyed” art, we ignore the centuries-long tradition of how economic circumstances have enabled art’s progress.

Think about the works we now consider all-time classics. Michelangelo did not do the Sistine Chapel ceiling as a work of self-expression. He was commissioned and paid by the Catholic Church. Handel’s Messiah was composed in the hope of ticket income.

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, now celebrated as a monument of artistic expression in our time, was funded by aristocratic patrons in the hope of gaining prestige by having their names associated with it. Even the design and construction of Saint Peter’s Basilica, arguably the most monumental work of architecture in history, was funded solely through commissions and donations from its backers. These works were not created in a vacuum outside the economic arrangements— they were made within them.

This dynamic endures today. Movies, television, music and online media are among the most ubiquitous forms of art in our era, and all are directly linked with capitalist markets. Hit feature movies, popular music recordings and popularly watched shows all react to popular demand, business investment and the ability of artists to create work audiences desire. Some have alleged that this system produces “formulaic” or “market-driven” art. Still, that critique misconstrues the dynamic that art has always had an audience, and pleasing that audience has never been absent from the equation. A Renaissance painter needed to please a patron paying his wages just as a filmmaker today requires viewers. The motivator is the same — art is in trade with its advocates.

In fact, among the most brilliant works of art were never made in anticipation of reward. Vincent Van Gogh’s “Starry Night” and Franz Schubert’s Ninth Symphony were written without great minds on material reward, and their beauty cannot be ignored. This suggests that art is not solely motivated by capitalism — it does not, however, prove that it kills it. Instead, it shows the range in which art is a possibility. Both commissioned and personal work are capable of greatness.

The sort who say that capitalism corrupts art point to commerciality, claiming that money dilutes originality or depth. However, popularity and access are signs of decline — proof art is getting in front of more people than ever before. Pop culture is not necessarily “high art.” Still, it speaks to the multitudes, just as folksong, street corners and traveling stage plays did.

Capitalism has not eliminated art. Capitalism shaped, funded and popularized it. Capitalism ensures the persistence of art; as long as individuals are willing to listen, there will be artists who find a way to make it work.