One plucky team and two crashed drones were part of what led to a $5 million cash prize to Limelight Rainforest. Hosted by XPrize, nearly 300 teams were tasked with the seemingly impossible quest of quantifying the vast biodiversity of the rainforest.

“I think we were probably the only team at semi-finals who really had no expectation of getting to finals,” said Team Leader and professor of biology at Colorado Mesa University (CMU) Dr. Tom Walla. He assembled what he called a scrappy and passionate team that cares about saving the rainforest.

“It was very rewarding and left us in disbelief for a while,” said CMU biology senior Taylor Schmitz. “I sometimes still cannot believe we won.”

Schmitz joined the team in March of 2024 and worked closely with CMU biology professor Dr. Denita Weeks. They were part of the team that sequenced DNA found in the rainforest.

Beating out nearly 300 other teams from around the world through three rounds, CMU’s team Limelight Rainforest reigned supreme.

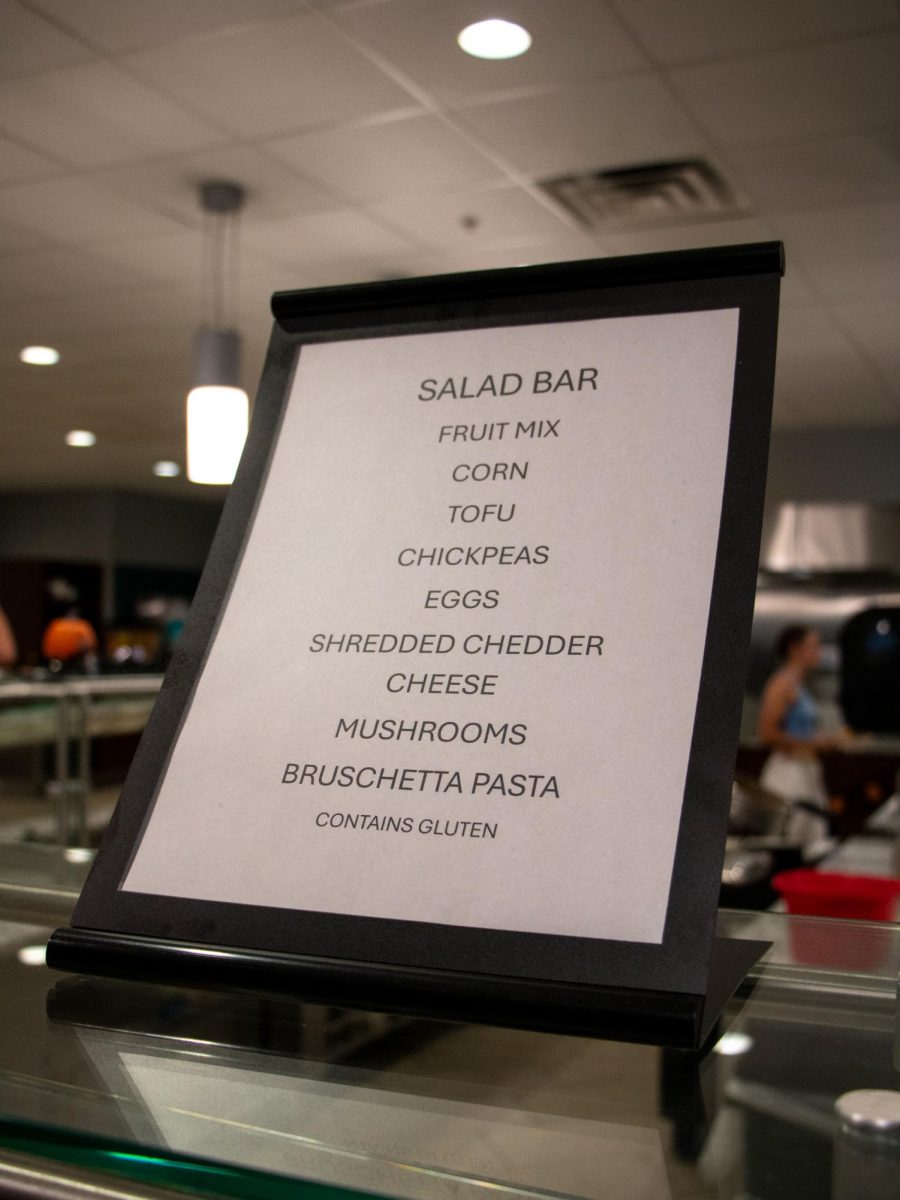

The name of the game was collecting samples of everything possible: images, bird calls, DNA from dung, leaves, branches and even water scum. Teams scrambled to find the most efficient way to collect and identify as many unique specimens as possible within a 72 hour window.

XPrize had a unique stipulation; no people were allowed within 200 meters of the testing sites. This means all the collection devices had to be remote operated.

“There were a lot of ground robotics teams at semi-finals,” said Walla. “And not all of them failed, but I could never imagine a robot that could walk through a rainforest. Took many sticks.”

After making it through semifinals last semester, the six remaining teams were given a $300,000 waypoint prize and Walla said that supercharged everything from pace to passion.

Similar to Thomas Edison’s pursuit of the lightbulb, Walla described a litany of testing to create a device that comprehensively captured biodiversity in rainforests. He knew he wanted to use drones to deploy the devices but he said it took some trial and error to find the right collection method.

It started with a device dubbed the “treehugger” that hooked around a tree and collected samples in a device that raised and lowered.

The team moved on to collecting bugs and sequencing DNA found in their dung. While those sampling techniques worked, the team found that they weren’t casting a wide enough net.

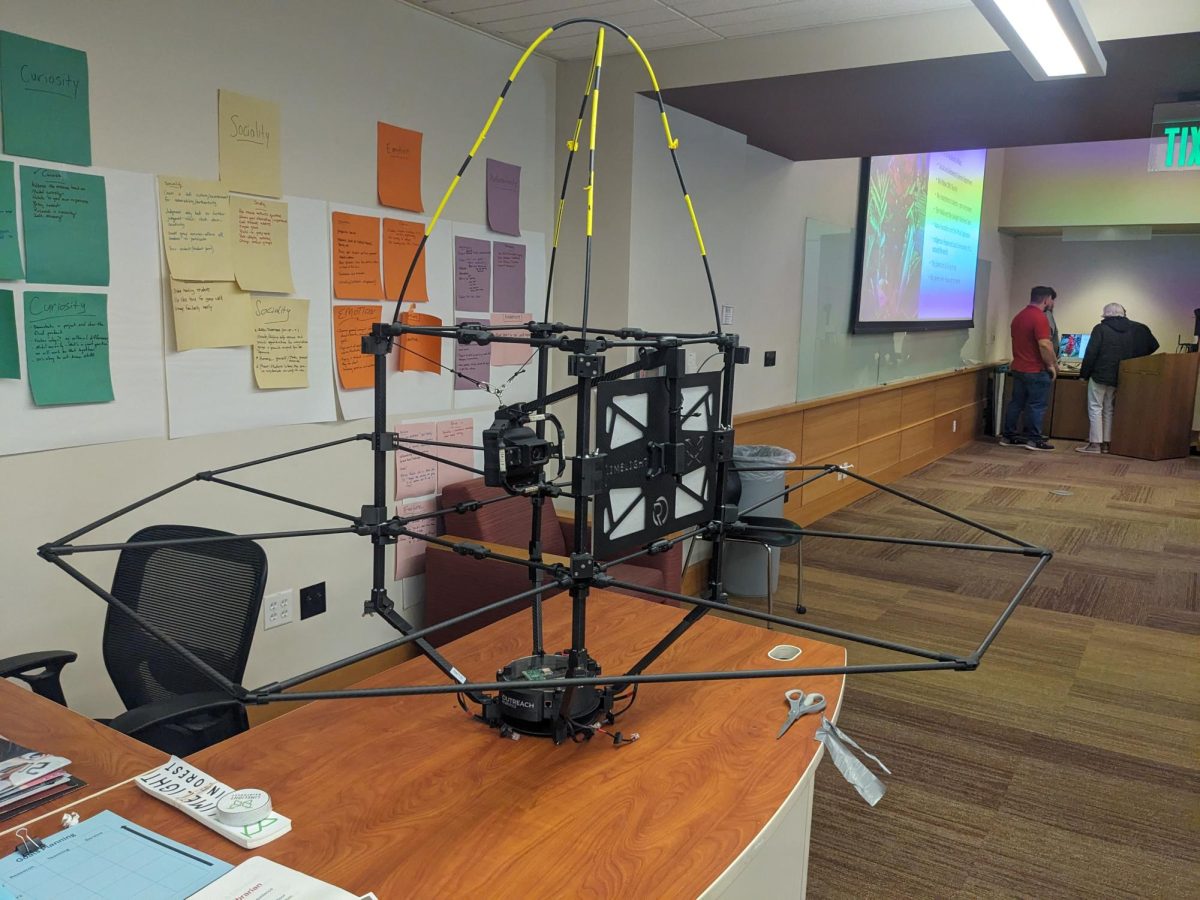

This is where the Limelight rafts came into play. The genesis of the team’s name came from these tent-like contraptions, or rafts, that drones placed into the rainforest canopy. 10 were deployed during the final competition to collect insects, images and sound recordings of the rainforest.

Images and live specimens used for identification are common tools for biologists. Striving for more, the Limelight team developed an acoustic system that spatially tracked birds while making their call in flight. Walla said that type of tracking had never been done before. It was one of the biggest changes between semi-finals and finals.

They also deployed sampling devices that collected eDNA or environmental DNA from water filters. A relatively new field, eDNA has the potential for collecting high concentrations of unique samples.

“Any organism that moves through the environment leaves cell traces: skin cells, hair cells,” said Walla. “If they’re in water, [it] can transport down the watershed to a centralized part of the water flow area. So that includes walking in water, pooping in water, flying over water, dropping a feather in water, water washing off of leaves and into the water.”

According to Walla, collecting the samples was just one piece of the puzzle. Identification and cataloging everything was the other. Schmitz was part of that team in Brazil during finals in July and she said being adaptable was the most challenging part.

“In March I started as someone who had little to no lab experience aside from classes and who didn’t know much at all about DNA sequencing,” said Schmitz. “By May I had to be proficient in my role and by July I had to be perfected to keep up with the pipeline and get everything done that we needed to in the 72 hours we had.”

That adaptability and hard work seemed to pay off exponentially. Walla said that during semi-finals they identified six trees, but in finals, they counted a whopping 23,000. Similarly, the team went from identifying a few insects during semis to hundreds for finals.

“We barcoded over 1400 sequences in just under a week,” said Schmitz. “This, for comparison, took the Smithsonian a couple years to do.”

While other teams did essentially the exact same thing as Limelight Rainforest, Dr. Walla believed that genuine interest in conservation and individual agency truly set them apart from others. Up against teams composed of mostly faculty from some of the most prestigious schools in the world such as ETH Zurich, Purdue University and Yale University, Limelight Rainforest proved that passion prevails.