Features Reporter, Managing Editor

Illustration by Hannah Wilson

“The key to beer is happy yeast and fresh sugar,” said Tim D’Andrea, avid home brewer. While relying on a concrete routine, brewing is a scientifically- intensive process extending far beyond measuring ingredients.

D’Andrea also happens to be a chemistry professor at CMU, and his passion for practicing and understanding chemistry couples with his love of beer, giving him an edge in understanding the diverse and oftentimes cantankerous process.

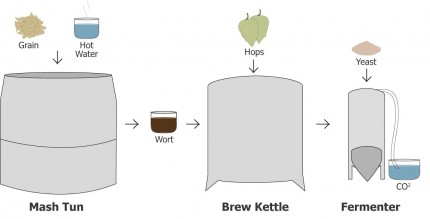

To start the process, you have to “make a tea out of your barley,” according to D’Andrea. Starting in a metal vat, called a mash tun, which is filled with hot water and a blend of grain that contains sugars, starches and various other flavors, compounds are extracted.

Roasting grains affects their overall flavor. Different flavors from grain result from the amount of roasting they undergo. Heavy-roasted barley tastes a lot like coffee beans with a hint of chocolate, and it brings that flavor with it to beer. However, the more a grain is roasted, the less natural sugar it has, sugar that will eventually be converted to alcohol. Blending grains of various roasting levels is crucial to the overall flavor of a beer.

Once the “tea” has been properly steeped and drained from the tun, it can now be referred to as wort, what D’Andrea calls “sugar water,” which is then heated in a brew kettle to rid the mixture of bacteria and help some sugars caramelize or otherwise develop into more complex flavors.

Extract syrups, which contain a concentrate of wort, can be purchased and used by brewers. Mixing this extract with hot water generates an insta-wort, skipping the initial steeping process altogether.

“You have a lot less control over the final product,” D’Andrea said about the extracts, which don’t allow brewers as much control of the specific blend of grain in their wort. He assures that overall quality isn’t affected, but the beer will be less unique.

Once in the kettle, hops get added. Hops are the female flower from the Humulus lupulus plant. They add bitterness, flavor and aroma to beer.

Hops added before the heating process lose most of their bitterness but contribute flavor and aroma, whereas hops added after wort has cooled, before going into the fermenter, are responsible for more bitter flavors in beer.

Compounds known as alpha acids in hops undergo a structural change called isomerification to become iso-alpha-acids. These acids are a fundamental part of the bitterness of beer. Calculating the parts-per-million (PPM) of iso-alpha-acids in a beer results in the International Bitterness Unit (IBU) of the brew, which translates to the beer-savvy consumer as the level of bitterness and texture of the consumed product.

Beers with more hops, and more iso-alpha-acids, are more prone to “skunking,” as D’Andrea puts it, where iso-alpha-acids react with light and become sulfides, which can result in off-flavors. To avoid skunking, beers are bottled in brown bottles that don’t let a lot of light in or canned, helping to improve their flavor through various lengths of shelf life.

After the wort has been heated and subsequently cooled in the kettle and hops have been added, it’s time to add yeast and head to the fermenter.

Equally complex as blends of grain and reactions concerning hops, “every yeast is it’s own beast,” Pete Jeffryes, assistant brewer at Kannah Creek Brewing Company, said.

Yeast is the primary activator of fermentation, a metabolic process by which yeast consumes sugar and produces ethanol and carbon dioxide. According to the brew staff at Kannah, the average fermentation takes about two weeks.

Yeast conducts itself differently dependent on temperature, and different kinds of beer require different types of yeast. Ale yeast, which is also used for porters and stouts, is “top cropping,” which means it rests and carries out its metabolic process at 66-69 degrees Fahrenheit at the top of the fermenter.

Lager yeast, which carries its process out on the bottom of the fermenter, spends most of its time around 50 degrees. Lagers also require a longer aging process after fermentation, so that proper flavors can develop.

No matter how long fermentation takes for a particular beer, the brew doesn’t just get sealed up and left to its own devices within the fermenter.

“Every day we test under a microscope for yeast cell content,” Emma Dutch, head brewer at Kannah Creek, said.

Pulling out a microscope and slide with a specialized grid, Dutch explained how samples of beer are placed on the slide, which reflects one milliliter of liquid, and the yeast cells, which show up as tiny ovals, are counted. These concentrations relate to the internal processes of the fermenter, and help brewers make decisions about temperature alterations so that a beer matures in the way its intended to.

Yeast can be pulled from active fermentations and also filtered post-fermentation and stored in a cooler where “they kind of go into a hibernation state,” Dutch said.

This yeast is still alive, and it can be re-used to make similar beer. As the organism lives and propagates within a single fermentation, it will carry on similar processes in others.

“We’re on generation 15 with our in-house ale strain,” Dutch said.

Brewing is “by no means an exact science,” Dutch said. “Even brewers who brew for 50 years learn new things every day.”

“It’s the difference between a brewpub and a production brewery,” Jeffryes said.

Kannah owns its own production facility, the Edgewater Brewery, which bottles the company’s most-popular brews. Daily communication is necessary to exact the craft techniques from the small brewpub at the production brewery. According to Jeffryes, the methods are the same, but the scale is larger.

D’Andrea says when he started home brewing, he brought his chemistry knowledge with him.

“I was really scientific about it. I used to try and control everything.” D’Andrea said. However, when it comes to craft brewing, unlike mass-scale production brewing, some variance is accepted.

D’Andrea still tests his beer for ABV and IBU, as he does for Kannah Creek and the Rockslide brewing companies. That’s as far as he goes, though.

“I like the idea of each beer being unique,” D’Andrea said. “A basic idea is a really useful thing to have, but a detailed understanding isn’t necessary.”

Whether the craft is extremely exact or the heavy scientific lifting has already been done and extracted, the process of creating unique beer relies on an extremely diverse set of variables. Variables that can be altered and modified with only one end result in mind; good taste.

ealinko@mavs.coloradomesa.edu.com

Recent Comments